As part of the continued quest for health care that is more person-centred, holistic and which acknowledges social determinants, there are ongoing shifts to develop service models and models of care which are sensitive to the whole-of-person factors which contribute to overall wellbeing. One emerging innovation is social prescribing.

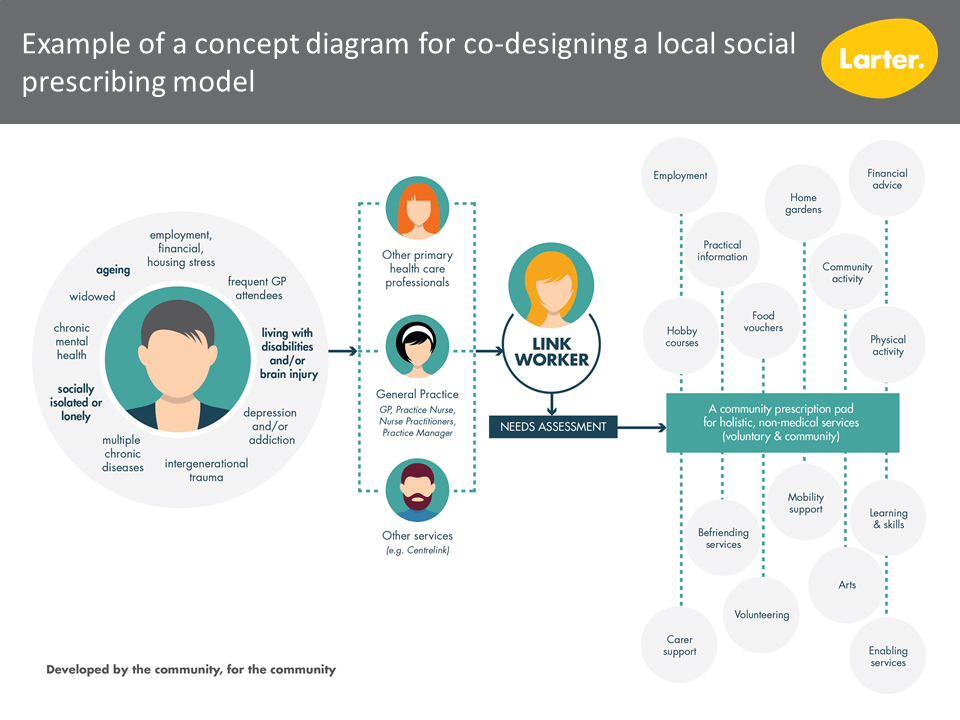

Social prescribing can be summarised as a process where a healthcare worker refers a patient to a link worker who assesses their needs and provides a non-medical prescription to improve their health and wellbeing. For example, this might be to social activity; to information or guidance; to a community group; or to learning and skills.

One way of understanding this is through a place-based lens, which recognises the relationship between person and place: that is, recognises that people and places are inter-related, and that the places where people live and spend their time affect their health and wellbeing. Of interest here is finding ways to draw on the existing strengths of our communities – increasing connectedness to the various community and voluntary groups and services which already exist.

We know from international settings that social prescribing has shown some promising outcomes.

We know for example that one in four Australians are experiencing loneliness, and that many people are socially isolated, or experiencing stress from work, financial or housing problems. Many others are living with depression, addictions, chronic illness or the experience of trauma. Studies have shown benefits from social prescribing for numerous population groups. Whilst in international contexts, the focus is often on isolation, and creating social linkages, there are many more powerful applications of the concept. The key is to develop a model that is responsive to local community need.

We have seen that people with social prescriptions get better and feel better faster than people treated with medications alone. Prescriptions are driven by a thorough understanding of individual needs, which in turn provides more control for individuals over their own health care. International experience with social prescribing has seen outcomes in:

- reduced emergency department usage

- reduced inpatient admissions

- reduced general practice over-attendance

- reduced GP workload

At its most basic, the premise is to encourage doctors to think beyond the prescription pad. At its most sophisticated, it is about the opportunity to address underlying, and sometimes long-term, lifestyle and behavioural issues and motivations. We have yet to really understand and meaningfully apply this.

One area of opportunity is to explore how this model can tackle entrenched disadvantage in low socioeconomic areas. Another is psychological distress and obesity.

In looking at local Australian contexts, there are many considerations in developing models or approaches that are purpose-fit. For example,

- engagement or motivation of hard-to-reach or most-vulnerable individuals with the concept

- translating the concept (including the name, the link worker concept, the ‘social prescription’ pad) for the local community/ies

- community health literacy around social determinants (ie understanding of the impacts of life conditions or contexts on health outcomes)

- availability of community and voluntary resources to meet social prescription needs

Key is to be able to connect people to non-clinical services based on their need. In Australia, we have already begun to think this way in recovery-oriented approaches to complex mental health, and in disability support through the NDIS.

At individual level, the general outcomes which social prescribing can offer include:

- improvements in self-reported health and wellbeing

- improved self-management skills

- increased physical activity

- reduced demand on medical professionals to deal with non-medical conditions.

Primary Health Networks and other co-ordinating, reform, innovations and funding bodies need to look at what this could and should look like in their local communities and work with the local community to co-design best-fit local approaches to trial.

Contact us if you’d like to explore what social prescribing could look like in your community.

February 2019.