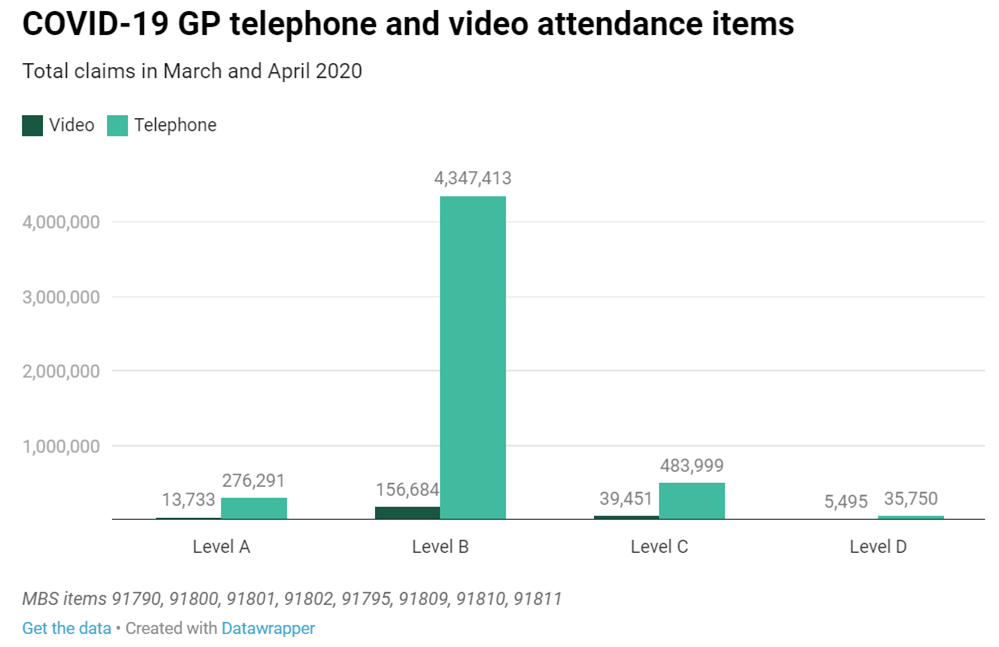

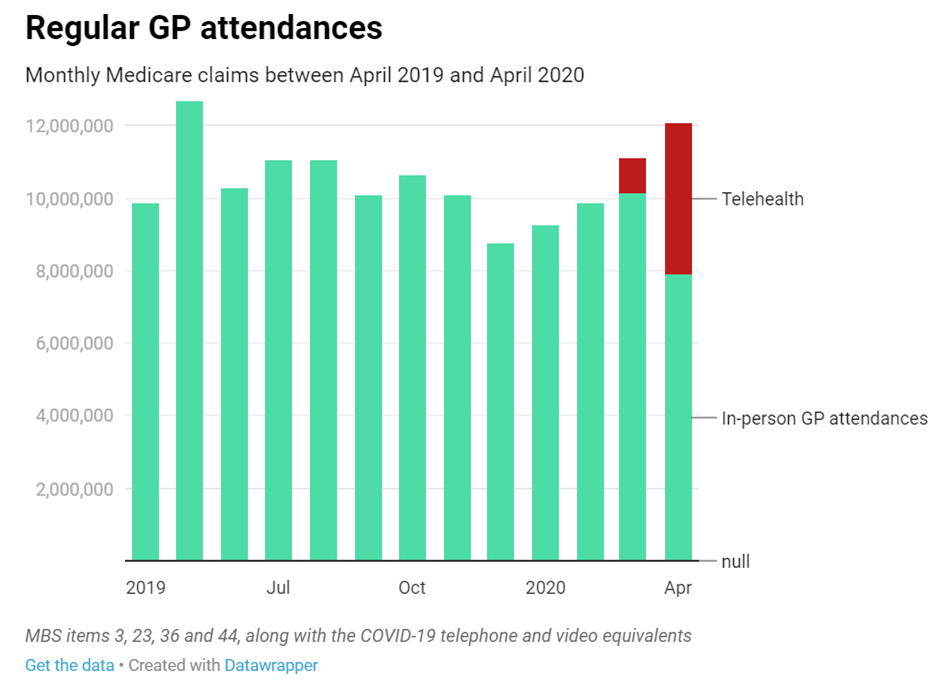

Advocates of telehealth have long suggested that it has the potential to address many of the challenges of delivering health care in a country as vast as Australia. But it took the COVID-19 pandemic to rapidly shake-up technology and funding systems and prompt uptake by necessity from both providers and consumers. ePrescribing and medicine home delivery initiatives have also been introduced, complementing telehealth consultations. As a result, more than 12 million consultations have been conducted by telehealth since new MBS numbers were introduced in March.

Both of these graphs have been sourced from Revealed: How COVID-19 has up-ended GP Medicare billings (AusDoc)

Due to its popularity and the benefits for rural/remote Australians and in helping maintain social distancing, it seems increasingly likely that telehealth rebates will continue beyond September with the potential to permanently change the way health care is delivered.

Telehealth models of care must be evaluated to:

- help providers and consumers decide when to use telehealth (e.g. for which conditions, what part of the course of treatment, for what level of patient complexity)

- determine how telehealth has improved the efficiency and effectiveness of health services

- determine whether telehealth is improving the coordination of care (right care, in the right place, at the right time).

This is particularly important given that telehealth uptake has been so rapid in order to address a pressing current need without necessarily looking to the long term.

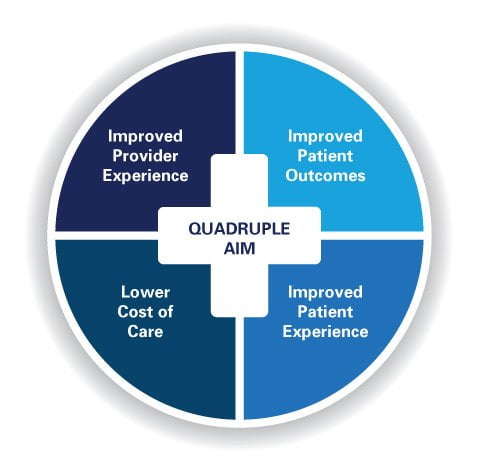

The Quadruple Aim of health care[1] provides a useful starting framework for evaluating new models of care – looking at how and whether patients, providers, populations and systems are benefiting from reform.

Below, we provide our thinking on some key considerations for conducting evaluation of telehealth models.

Accounting for patient experience

Early evidence suggests that patients generally have a positive experience using telehealth; but it’s not universally positive. While telehealth improves access for some, it has the potential to be exclusionary, particularly if used poorly by providers. Involving consumers in evaluations of telehealth systems is important in a rights-based, patient-centred healthcare system, and is also likely to lead to better quality evaluation findings. Often patients have the best ideas about how to improve their experience.

Consumer research is sometimes considered ‘too hard’ – it takes time and careful navigation of the challenges of ethics and consent. However, growing acceptance of the consumer voice in evaluation has led to the development of tools to improve patient feedback loops. Patient Reported Outcome and Experience Measures (PROMs/PREMs) can be built into service models and their accountability systems. This helps align patient and service goals – following the old adage that what is measured matters.

Using evaluation to support provider implementation

Anecdotally, we have been hearing that there are numerous factors driving providers’ experiences of telehealth, including:

- the nature of the telehealth platform and their comfort using it

- the relationships they have with patients

- the type of care they are providing.

Process evaluation is particularly important for understanding how telehealth is implemented and how these underlying factors drive adoption and success. Process evaluations look not just at the outcomes for patients, but at the logistics of implementation. For example:

- how effectively was telehealth set up and tested?

- as problems emerge, how are they addressed and overcome?

If telehealth continues to be funded – and becomes a patient expectation – it’s important that providers are enthusiastic about the potential of this technology, and are supported to effectively integrate it into their practice. This means considering factors such as how people engage (e.g. video- or phone conferencing) and how providers might need to change their consultation practice accordingly. Larter is currently using process evaluation for the use of My Emergency Doctor telehealth support for after hours care in regional and regional settings, working with both clinicians and consumers to answer implementation and adoption questions.

The challenges of assessing population health outcomes

A consistent challenge in evaluations of program-level initiatives is identifying whether they contribute population health outcomes. Change at the population level can be difficult to observe and even harder to attribute to a specific initiative, as it takes time and is subject to multiple influences. As a result, there is a tendency in health systems to measure output indicators. For example, we know the number and length of MBS telehealth consultations that have been billed, but very little about the content of those consultations and the likely health impact on consumers and communities.

Measuring outputs is not necessarily a bad thing, but outputs must be tied to an underlying logic of a program that identifies how and in what timeframe activities are likely to contribute to health outcomes. Telehealth was implemented incredibly rapidly in Australia, and when the dust settles, it’s worth pausing to consider how we develop monitoring systems underpinned by a theory of change. This is not simply to make evaluation easier, but ensures that the reporting burden for frontline services is targeted to the measures that tell us most about system performance.

A well-considered approach to data collection that ties activity to population outcomes, also enables comparison across service types and patient cohorts. This will help us to actually answer many of the questions that have arisen during rapid telehealth adoption, such as:

- which platforms are most effective

- which cohorts benefit or miss out from telehealth

- which service types have the greatest impact when delivered online.

Comparison of system-level outcomes supports funders and commissioners to target telehealth funding to the areas which achieve greatest consumer and community benefit.

Understanding the sustainability of telehealth

Telehealth has been introduced out of necessity, but we’re hearing claims that aspects of telehealth models implemented during COVID-19 may not necessarily be financially sustainable. In a health system with limited resources and thin profit margins, financial and economic evaluation (such as sustainability analysis or cost-benefit analysis) is essential.

It’s also important to consider how new service models can create perverse incentives. Some are already emerging from the COVID-19 telehealth rollout, such as the providers offering services for patients they have never met, meaning that treatment is being provided without vital measurements being taken, and inadequate incentives to provide non-emergency after-hours care. Evaluation should not just look at the realisation of anticipated outcomes, but provide mechanisms to explore what was not expected – positive or negative.

Telehealth in primary health has arrived in the mainstream, and it looks set to stay. It has been rapidly adopted in unlikely circumstances, and now its long-term funding and adoption must be well thought-through. COVID-19 has given providers a chance to rapidly test ‘what works’. This is evidence that, if used appropriately, telehealth can improve the rollout of other health improvement initiatives such as GP voluntary patient enrolment. We also have a chance to look beyond primary care, using the lessons here to explore the potential for telehealth to be a normal part of specialist outpatient care and allied health care.

To be most effective, telehealth must work for consumers, providers and the health system. As a result, effective evaluation must underpin future decision-making on telehealth. That means examining what currently works, what is not working, and looking for opportunities to improve.

By Jo Farmer, Associate Consultant and Jo Grzelinska, Principal Consultant

Contact us to discuss your telehealth model of care or evaluation needs.

[1] Bodenheimer, T. and Sinsky, C. 2014. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Ann. Fam. Med. 12(6):573-576. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4226781/

Primary image by Anna Shvets from Pexels